Summary of movement

The origins of the Islamic State—also known more widely as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) or the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL)—can be traced back to the US-led military invasion of Iraq in 2003. Its original incarnation, the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI), grew within a milieu of ideologically diverse militant groups that opposed the US and the post-2003 US-backed Iraqi administration. Like many other militant Muslim groups, often generalised as ‘jihadist’, the Islamic State rejects existing notions of the nation-state in favour of what it defines as the ultimate Islamic polity—the caliphate. What distinguishes the Islamic state from these other groups, alongside its unprecedented use of violence, is its claim to have already established this caliphate. The Islamic State is therefore a religiously motivated, insurrectionary movement that also behaves like a state, with its own bureaucracy, geographical territory, economy, and population. Underlining its military strategy and state-building ambitions, however, is a distinctive brand of Islamic apocalypticism.

History/Origins

Among the US-led military coalition’s enemy targets in the 2003 invasion of Iraq were the mujahideen, or veterans, of the anti-Soviet war in Afghanistan in the 1980s. In the Soviet-Afghan War, the mujahideen were backed financially, militarily, and politically by the US, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia. These fighters included Osama bin Laden, the Saudi-born leader of Al Qaeda who was behind the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, and the Jordanian-born Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi, who returned to Afghanistan post-9/11—this time to fight against, not alongside, the US. By 2002, al-Zarqawi had moved to Iraq and incited a series of violent attacks there in anticipation of the impending US-led campaign. After the invasion, al-Zarqawi pledged allegiance to bin Laden and became the leader of Al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI).

Relations between AQI and its parent group, however, were never great. Zarqawi often irked Al Qaeda’s top leadership—namely bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri—by leading or authorising what they saw as excessive brutality. The Al Qaeda leadership repeatedly chided Zarqawi for his disobedience and lack of communication (McCants 2015, 12–13). Yet during this period, both Zarqawi and the central Al Qaeda leadership began developing the idea of establishing an Islamic state in Iraq.

In 2006, Zarqawi was killed in a targeted US military strike, resulting in a leadership vacuum in AQI. Within months, however, the group announced the establishment of the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI), led by Abu Umar al-Baghdadi, its ‘Commander of the Faithful’. This honorific title is the Arabic style that many Muslim leaders have adopted throughout history to symbolise the legitimacy of their authority. For Sunni Muslims, this is understood as going back to the earliest caliphs, or political successors to the Prophet Muhammad after his death.

The idea of the caliphate has thus endured—and has been contested—throughout Muslim political history. The general view is that the caliphate, as an institution, met its demise after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. Yet throughout the history of Islam, there have been different polities that have claimed to be caliphates, including in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. In the twentieth century, several Muslim movements also emerged, advocating for a revival of the caliphate. The birth of ISI as a proto-caliphate was thus part of this development.

In public, Al Qaeda’s top leadership celebrated the announcement of ISI, leading many observers to regard it as a straightforward rebranding of AQI. In private, however, relations between Al Qaeda’s central leadership and ISI remained fraught (McCants 2015, 40). Bin Laden and his associates continued admonishing ISI’s leadership for poor communication and coordination. They despaired at ISI’s territorial losses and inability to marshal support from Sunni tribes against the Shia-dominated, US-backed Iraqi administration.

Also, Baghdadi’s influence seemed so marginal that in 2007, US officials thought he was merely an actor playing a fictional character (Yates 2007). By 2008, Al Qaeda regarded ISI as a failure and an embarrassment. In April 2010, Baghdadi and Abu Ayyub al-Masri—a key ISI leader—were killed in a joint US-Iraqi raid near Tikrit. Within a month, ISI appointed a new leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, who—like his predecessor—assumed the title of ‘Commander of the Faithful.’

The turning point for ISI was the Syrian civil war, which started in 2011. Jihadist leaders were already trying to claim credit for the Arab revolutions that were sparked off in Tunisia in late 2010. Al Qaeda’s Zawahiri even argued that it was the 9/11 attacks that laid the foundations for the success of the uprisings (Neumann 2016, 51), despite the generally civilian-led, non-Islamist character of the revolutions. However, the situation in Syria took a dramatically different twist.

In 2011, Baghdadi sent a contingent to Syria to form Jabhat al-Nusra (‘the Salvation Front’)—now known as Tahrir Al Sham (‘Levant Liberation Committee’) or Al Qaeda in Syria—which quickly became the leading Sunni rebel militant group there. At the time, the relationship between ISI and al-Nusra was not publicly acknowledged. In 2013, however, amid worsening acrimony between ISI and Al Qaeda, Baghdadi announced ISI’s expansion into Sham, which technically encompasses the entire eastern Mediterranean but which jihadists equate with modern Syria.

According to Baghdadi, this upgrading of ISI into ISIS or ISIL effectively dissolved and absorbed Al Nusra. The Al Nusra leadership opposed this, however, and appealed to Al Qaeda’s central leadership for support. Zawahiri quickly intervened and tried to annul ISI’s Syrian takeover, insisting that it and Al Nusra maintain separate jurisdictions. Baghdadi remained defiant, even as some Sunni militant groups in Syria opposed the idea of ISIS/ISIL and remained pro-Al Qaeda. This was accompanied by some behind-the-scenes attempts at reconciliation.

In mid-2014, Zawahiri publicly declared that ISIS was originally a ‘branch’ of Al Qaeda, having previously given its parent organisation bay’a, or an oath of loyalty. The implication was that if ISI was a subsidiary of Al Qaeda, then Baghdadi’s refusal to withdraw from Syria in 2013 amounted to insubordination. ISIS/ISIL, as the group referred to itself by this time, disputed that it had ever given bay’a to Al Qaeda (McCants 2015, 94). Instead, ISIS/ISIL proceeded to crush its enemies and made further advances in Iraq. By the end of June 2014, it conquered the city of Mosul and declared the caliphate there—ISIS/ISIL was now to be known as the Islamic State, with Baghdadi as its caliph.

From June onwards, the US intervened militarily against the Islamic State, at the request of the Iraqi government. Following this, the Islamic State began circulating the infamous videos of its various beheadings, including those of various Western aid workers and journalists. Starting from 2014, individuals or ‘lone wolves’ inspired by the Islamic State also began launching attacks in different locations in Western Europe, North America, and Australia. Alongside this, Islamic State-inspired attacks have since taken place in countries with Muslim-majority populations beyond the Middle East and North Africa, including Bangladesh, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

As of 2017, the actual size of the Islamic State is difficult to estimate (Neumann 2016, 70). Depending on how its ‘population’ is defined, this could range from 20,000 to 200,000. At its core, there are probably 30,000 to 40,000 members who have sworn an oath of loyalty. There are also the Islamic State’s helpers, or those who support and wear its insignia but have not made bay’a. Similarly, there are the tribal militias and other groups that cooperate with the Islamic State for now. According to some estimates, the Islamic State could muster 200,000 troops but not all of these would consist of fighters who have pledged sole loyalty to it.

In July 2017, the Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi formally declared victory over the Islamic State in Mosul after a nine-month battle waged by US-led coalition forces (BBC 2017). In September 2017, at the time of writing, the Islamic State’s Syrian stronghold, Raqqa, appears to be on the verge of being taken by the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) (Reuters 2017). Although these victories have been celebrated by the Islamic State’s US-backed opponents, the humanitarian costs have been huge. In the battle for Mosul, for instance, thousands of civilians were killed and around one million of the city’s residents are now displaced, many among them ill or malnourished (Tisdall 2017).

Additionally, the struggle for leadership in the Islamic State’s former centres of power in Iraq and Syria are filled with tension. In Syria, although the SDF was militarily backed by the US, it was bankrolled by the Syrian regime which, in turn, was supported by Iran and Russia (Van Wilgenburg 2017). Iran’s influence in Iraq also complicates matters there. In both countries, the role of the Kurds in repelling the Islamic State has also triggered developments that have alarmed the region’s geopolitical status quo. In September 2017, 93 per cent of those who participated in the Kurdish independence referendum in Iraq’s semi-autonomous Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) voted for a full split from Baghdad (McKernan 2017). Turnout was high, at 72 per cent out of a population of 8.4 million. The Iraqi government refused to accept the referendum, calling it unconstitutional. Neighbouring Iran and Turkey also vehemently oppose Kurdish independence.

Amid this ongoing turmoil, it was unclear whether a military defeat of the Islamic State translates into a decisive victory over its ideology or capacity for violence—perhaps even a revival—in the near future.

A short video explaining the origins of the Islamic State can be viewed here

A two-part documentary on the rise of the Islamic State, produced by the news network Al Jazeera

Beliefs

In many journalistic and academic works, the Islamic State has been described as ‘Salafist jihadist’ or ‘Wahhabist’ (for example in Bunzel 2015, 7 and Cockburn 2015, 98–99). These characterisations evoke the group’s extreme and apparently inflexible interpretation of Islam. Although not entirely helpful, this labelling is understandable, given the doctrinal sources the Islamic State draws upon. In the early days of the caliphate, for example, its classrooms used textbooks from Saudi Arabia—the birthplace of Wahhabism (Olidort 2016, 9).

Wahhabism

Wahhabism refers to the religious movement founded and inspired by the eighteenth-century reformer Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. Emerging in the Arabian Peninsula, its main objective was the purification of faith and worship. At the same time, Ibn Wahhab formed a pact with Muhammad bin Saud, culminating in the founding of the first Saudi state in 1744. This ended in 1818, after the Ottoman-Egyptian invasion (Al-Rasheed 2007, 2). Wahhabism survived, however, because its leaders moderated their religious zeal and supported political power. Their subservience ensured their survival during the similarly short-lived second Saudi state (1824–1891) and the current Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (established in 1932, after a process of unification starting in 1902).

Wahhabism is not straightforwardly pro- or anti-Western. In 1915, for example, the House of Saud signed a treaty with Britain, effectively turning it into a British protectorate (Al-Rasheed 2007, 10). Subsequently, Wahhabi doctrines have been vehemently opposed to ‘infidels’ and ‘deviant’ Muslims yet have also supported the Saudi regime’s close alliance with Western powers.

Salafism

The term Salafism is often used interchangeably with Wahhabism. It can be understood as an approach to Islam that invokes the literal interpretation of religious texts and a return to the traditions of the pious companions of the Prophet Muhammad (al-salaf al-salih). ‘Salafiyya’ can also refer to a modernist-reformist movement in the nineteenth century led by figures such as Muhammad Abduh (1849–1905), the Egyptian scholar and jurist. However, this liberal or modernist variant of Salafism was neither politically quietist nor doctrinally literalist, and has very little in common with Wahhabi-style Salafism (Al-Rasheed 2007, 3).

Even in Saudi Arabia, ‘Salafi’ and ‘Wahhabi’ are contested terms. Salafism can therefore best be understood as an elastic identity. In the West, most Salafi groups are non-violent, and neither are they clandestine—Salafis are well-known for their eagerness to explain their teachings to anyone who is interested (Inge 2017, 8). However, aspects of Salafi teachings—which are extremely rigid—are shared by certain jihadist groups in Sunni Islam, with some explicitly invoking the Salafi label to endorse violence. Thus, labelling the Islamic State as a ‘Salafi’ or ‘Salafi-inspired’ group does very little to explain its beliefs and actions, except to indicate the transnational, adaptable, and fragmented qualities of Salafism. Besides, some of the Islamic State’s most vociferous, albeit pacifist, opponents are Muslims whom some commentators carefully distinguish as ‘quietist Salafis’ (Wood 2015). Yet, because of widespread ignorance about intra-Salafi diversity, ‘quietist Salafis’ are also often viewed with suspicion and even hostility in the West as well as among many non-Salafi Muslims.

Jihadism

The term ‘jihad’ is similarly contested. Although it can refer to ‘holy war’, its semantic meaning in Arabic basically means to strive, exert, or take extraordinary pains. In the Islamic tradition, the term ‘jihad’ is often used without any reference to warfare. ‘Jihad of the heart’, for example, is about personal struggle against sinful inclinations, while ‘jihad of the tongue’ is about speaking out in favour of the good and forbidding evil. Nevertheless, when used without qualifiers such as ‘of the heart’ or ‘of the tongue’, ‘jihad’ is universally understood as religious war within the Islamic tradition (Firestone 1999, 17).

As a term to describe militant Muslim groups, ‘jihadism’ is a modern, Western coinage. Yet instead of using ‘jihadism’ as a label for a supposedly inherent aspect of Islam, it is more useful to understand it as a modern phenomenon intersecting with other contemporary Muslim trends. It is also a product of globalisation that shares some aspects in common with other anti-globalisation or anti-Western movements (Firestone 2012, 266).

Contextualising the Islamic State

These understandings of the modern, adaptable, and contested character of jihadism, Salafism and Wahhabism can help us understand the Islamic State’s apparent contradictions. Like its parent organisation, Al Qaeda, the Islamic State’s official doctrines do not differ greatly from those of Saudi Arabia, which it nevertheless considers an enemy state. For example, its hudud (Islamic criminal law) penalties are nearly identical to those upheld by the Saudis: death for blasphemy, homosexual acts, treason, and murder; death by stoning for adultery; one hundred lashes for sex out of wedlock; amputation of a hand for stealing; amputation of a hand and foot for bandits who steal; and death for bandits who steal and murder (McCants 2015, 136).

At the same time, the Islamic State refers to the writings of Ibn Wahhab to discredit the Saudi kingdom, accusing it of reneging on Ibn Wahhab’s legacy by colluding with the West (Olidort 2016, 26–27). It also relies upon writings outside the Salafi canon to provide doctrinal justifications of a caliphate, its methods of state administration and its use of extreme violence (Olidort 2016, 12).

The main difference between the Islamic State and Al Qaeda is that the latter focuses upon defeating Western powers—or the ‘far enemy’—before the caliphate can be established. The Islamic State, on the other hand, insists on vanquishing ‘near enemies’—namely Muslim governments that collude with the West and Shia Muslims—by establishing the caliphate first (Bunzel 2016, 13). Underlining this difference between the two groups is also the Islamic State’s far more explicit apocalypticism.

Millennial Beliefs

Before 2003, Sunni apocalypticism was a fringe phenomenon among most Muslims. Taking End-Times prophecies seriously was usually stereotyped as a preoccupation of Shia Muslims, or ‘uneducated’ Sunni Muslims. However, the invasion and military occupation of Iraq triggered immensely popular publications about the End-Times amongst Sunnis. The US and its allies were cast as the ‘new Crusaders’ or the new ‘Rome’, amid speculation of the coming of the Mahdi (messianic redeemer), and books that were commercial failures in the 1990s became bestsellers after 2003 (McCants 2015, 145).

Al Qaeda’s leaders, however, hardly mentioned any apocalyptic prophecies in their propaganda, probably due to their generational and class background. Bin Laden and Zawahiri grew up in elite Sunni families in which messianic speculation was viewed with disdain. Their attitude was encapsulated in an article distributed by an Al Qaeda propaganda outlet: ‘Many people think that the State of Islam will not be established until the Mahdi appears. They neglect to take action, instead raising their hands in prayer that God will hasten his appearance’ (McCants 2015, 28).

Still, there were Al Qaeda members who held strong apocalyptic beliefs, such as Abu Mus’ab al-Suri (a Syrian) and Zarqawi (the founder of Al Qaeda in Iraq). To Zarqawi, the Antichrist consisted of the Shia, in collusion with the Jews and Christians, fighting to oppress the Sunnis. After his death, Zarqawi’s successor Abu Ayyub al-Masri rushed to establish the Islamic State of Iraq in 2006 in anticipation of the Final Hour (McCants, 2015, 146).

The Quran itself contains scant detail about the End Times. It tells us that we cannot know when the end of the world will come but lists some events that will happen beforehand. These include the release of Yajuj wa Majuj (Gog and Magog), the emergence of a beast, the sky bringing forth clouds of smoke, and what has usually been regarded as a reference to Jesus’s return. The detail of End-Times prophecies can be found in the hadith, or recorded sayings of the Prophet Muhammad—ranging from phrases of a few words to passages equivalent to several pages (Beattie, 2013, 89–90).

The Islamic State draws upon these apocalyptic prophecies to construct its own vision of the caliphate and the Mahdi, and to justify its brutality. It reinforces this message via the manipulation and distribution of specific symbols in its propaganda material.

In Kirkuk, 2014, for example, ISIS (as it was known then) erected a billboard proclaiming: ‘The Islamic State: A Caliphate in Accordance with the Prophetic Method.’ This slogan refers to the following hadith (McCants 2015, 163–164):

Prophethood is among you as long as God wills it to be. Then God will take it away when He so wills. Then there will be a caliphate in accordance with the prophetic method. It will be among you as long as God intends, and then God will take it away when He so wills. Then there will a mordacious monarchy. It will be among you as long as God intends, and then God will take it away when He so wills. Then there will be a tyrannical monarchy. It will be among you as long as God intends, and then God will take it away when He so wills. Then there will be a caliphate in accordance with the prophetic method. Then he [the Prophet] fell silent.

This prophecy is popular amongst many jihadists because it vindicates their quest to establish the caliphate. However, for most of them, this is a relatively distant goal—the caliphate will only be restored once Muslims unite and regain their former glory.

The Islamic State innovates on this prophecy—through its own Grand Mufti (juris-consult), Turki ibn Mubarak al-Binali (McCants 2015, 115–17)—by highlighting another hadith that prophesies the emergence of twelve caliphs from the Quraysh, or the Prophet Muhammad’s tribe. Binali tweaks this hadith to place Baghdadi within this lineage.

Binali also claims that the Islamic State satisfies the conditions for a caliphate in that it possesses power, authority, and control of territory. On the last point, he argues that the caliphate does not need to extend over all Muslim lands—examples from Muslim history include the Umayyad revival in Andalusia and the Abbasids in Baghdad. Separately, Binali justifies why Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi is the rightful caliph—vaunting his lineage (as a descendant of Ali, the Prophet Muhammad’s cousin/son-in-law), religious credentials (as Baghdadi has a PhD in Quranic studies), and leadership experience during the early days of the invasion of Iraq.

Proclaiming Baghdadi as a caliph as distinct from the Mahdi has had the effect of prolonging the Islamic State’s apocalyptic expectations and directing its fervour into state-building efforts. The practicalities of this venture have thus reduced the Islamic State’s immediate zeal for the Mahdi even as its apocalyptic rhetoric intensifies. Its propaganda materials are filled with references to the End Times—which are particularly persuasive in attracting foreign fighters (McCants 2015, 147).

The Islamic State uses these and other religious symbols selectively to enact and emphasise its authenticity—something other jihadist groups also do. Its flag, for example, is inspired by traditional accounts that the Prophet’s flag was a black square made of striped wool. The flag’s colour also resonates with another set of apocalyptic hadiths of soldiers fighting under black flags coming from the East (Beattie 2013, 89):

The People of my House shall meet misfortune, banishment, and persecution until people will come from the east with black flags. They will ask for charity but will not be given it. Then they will fight and be victorious. Now they will be given what they had asked, yet they will not accept it but will finally hand it (the earth) over to a man of My Family. He will fill it with justice as they had filled it with injustice. Whoever of you will live to witness that, let him go there even though it be by creeping on snow.

Al Qaeda’s flag is also black and emblazoned with the shahada (declaration of faith: ‘There is no god but God, Muhammad is the messenger of God’). The Islamic State, however, uses a design adapted from a seal of the Prophet that appears on letters supposedly written on his behalf, kept in Topkapi Palace in Turkey. Modern scholars doubt the authenticity of these letters—a point the Islamic State disregards (McCants 2015, 20).

What complicates matters is that there are specific places named in various End-Time prophecies, with many located around Damascus in modern-day Syria (McCants 2015, 100). This is why Islamic State forces fought viciously to gain control of Dabiq in northern Syria, despite its lack of military importance. In fact, the symbolic importance of Dabiq was first expressed by Zarqawi, based upon the hadith (McCants 2015, 102–3):

The Hour will not come until the Romans land at al-Amaq or in Dabiq. An army of the best people on earth at that time will come from Medina against them. When they arrange themselves in ranks, the Romans will say: ‘Do not stand between us and those [Muslims] who took prisoners from among us. Let us fight with them.’ The Muslims will say: ‘Nay, by God, how can we withdraw between you and our brothers.’ They will then fight and a third [part] of the army will run away, whom God will never forgive. A third [part of the army], which will be constituted of excellent martyrs in the eye of God, will be killed and the third who will never be put to trial will win and they will be conquerors of Constantinople.

In 2014, the Islamic State published its own magazine, titled Dabiq in reference to this prophecy. In 2016, the magazine was renamed Rumiyah (Arabic for Rome)—probably in relation to Islamic State forces being driven out of Dabiq by the Turkish army and Syrian rebels. The new title refers to a prophecy about the fall of Rome.

The Islamic State also relies upon these apocalyptic prophecies to justify and promote its use of extreme violence. When it beheaded Coptic Christians in Libya in 2015, it claimed that this was part of a war with Christianity that would last until Jesus descends from Heaven (McCants 2015, 106).

The persecution of religious minorities represents not just the Islamic State’s eagerness to establish its version of Islamic law—it is also about catalysing the End Times. An example would be its treatment of the Yazidis, who have long been regarded by many Muslims as devil worshippers because they believe that the devil was a fallen angel who eventually repented. In 2014, the Islamic State announced that it had captured Yazidi ‘virgins’ and was selling them as sex slaves to its members (McCants 2015, 112). It heralded the return of slavery as a sign of the coming Day of Judgement based on the hadith: ‘One of the signs of the Last Hour is that the slave-girl will give birth to her master.’ The prophecy itself is ambiguous about slavery, but according to the Islamic State the logic is clear—slavery is currently prohibited, so a slave girl giving birth to her master must mean that slavery will return.

Apocalyptic beliefs are thus central to the Islamic State’s propaganda, state-building, and violent campaigns. At the same time, they demonstrate the Islamic State’s selective and creative appropriation of beliefs that are often simplified as Salafi-inspired jihadism, alongside apocalyptic prophecies that became popular only after the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Practices

The Islamic State is generally associated with extremely brutal violence against various groups and individuals, including Western aid workers and journalists, Coptic Christians, Yazidis, Shias, and other Muslims whom it considers traitors or deviant. Since 2014, it has also embarked on low-tech, improvised attacks in many Western metropolises—using bombs, guns, knives, and even motor vehicles as weapons. It has justified these either as jihad or as part of the implementation of hudud in the territories it controls. Yet its use of violence differs from that of other jihadist groups in some crucial ways.

Fundamentally, the Islamic State is not interested in winning the hearts and minds of the majority of Muslims in the world (Neumann 2016, 68). This is what caused its rift with Al Qaeda, which favoured an approach that would gain widespread Muslim support before trying to establish the caliphate. Al Qaeda leaders were not necessarily opposed to the Islamic State’s punishments, for example the beheading of enemies, but felt that these should not be broadcast so brazenly. Also, Al Qaeda still considered jihad a defensive strategy whereas the Islamic State’s approach was more offensive (Bunzel 2015, 10). Despite these misgivings, the Islamic State continued with its own brand of violence and eventually unleashed this upon its erstwhile jihadist allies.

Violence is also a state-building strategy and an opportunity to flex religious muscle. The Islamic State’s jurists often respond to their Muslim critics by quoting scriptural passages that appear to support their actions, almost as though they are brandishing their scholarly dexterity (McCants 2015, 137). For example, the Islamic State imposes heavy punishments for smoking—from fines to whipping and even death for repeat offenders—even though the practice is tolerated in much of the Middle East (McCants 2015, 139). In effect, violence is institutionalised within Islamic State—their annual reports even include the numbers of political assassinations and suicide bombings carried out during the year. The June 2014 report, for example, listed 7,681 operations, including more than 1,000 political assassinations and 250 suicide bombings—a significant rise compared to the year before (Neumann 2016, 78).

Controversies

From the perspective of the mass media in the West, the violence of the Islamic State is exceptional because of its unpredictably low-tech, improvised nature and its perpetration by ‘home-grown’ recruits—this was true of the attacks in Paris, Orlando, Brussels, Manchester, London, and other cities. Its spate of beheadings of foreign captives from 2014 to 2015 was also shocking, yet these developments were part of a larger, evolving trajectory of violence.

This violent pathway can be traced back to the Islamic State’s roots in Al Qaeda and the US-led invasion of Iraq. In particular, Camp Bucca—a US-run detention centre in Iraq—helped to forge new relationships between jihadists and Baathist supporters of Saddam Hussein. This complexity in Camp Bucca’s population was exacerbated when large numbers of detainees were transferred there after revelations of torture and abuse at Abu Ghraib, another US-run prison. Camp Bucca held up to 24,000 inmates and became known as the ‘Academy’ (McCants 2015, 75). After they were released, the mix of the jihadists’ ideological determination and the Baathists’ military expertise informed the growth of the Islamic State—Baghdadi, the Islamic State’s current caliph, was also a Camp Bucca detainee.

In 2014, the year it began grabbing headlines in the West, the Islamic State also made inroads into Saudi Arabia. It carved the Kingdom up into three ‘provinces’—Najd Province in central Arabia, Hijaz Province in western Arabia, and Bahrain Province in eastern Arabia (not to be confused with the modern state of Bahrain—‘Bahrain’ is an old term for eastern Arabia) (Bunzel 2016, 11). Suicide bombers targeted Shia mosques and Saudi security forces.

The Islamic State’s targeting of ‘near enemies’ and religious minorities is inextricably linked with its apocalyptic beliefs. Up until 2014, its campaigns were largely focused within the Middle East. However, it revised this strategy almost immediately after the US-led military campaign in August 2014. In 2014 and 2015, its official spokesman Abu Muhammad al-Adnani called on supporters to kill Westerners all over the globe—Americans, Canadians, Australians, and their allies, both civilians and military personnel (Bunzel 2015, 36).

In doing this, the Islamic State also departed from Al Qaeda’s more traditional mode of militarism—whereas Al Qaeda regarded ‘lone wolf’ attacks as failures compared to 9/11, the Islamic State actively encourages these. It advocates improvisation, including smashing people’s heads with rocks, wielding knives, using cars or other vehicles to run people over, throwing victims off high places, and even choking or poisoning them (Neumann 2016, 132). Even so, it grounds this advice on improvised violence within doctrines of war that can be found in traditional Islamic sources (Wood 2015).

Considering their inexperience, Western recruits are not as much of a military asset to the Islamic State compared to local fighters in the Middle East. Their value lies in their willingness to perform tasks that other Middle East-born fighters would be reluctant to do—primarily suicide bombings and beheadings. It is estimated that 70 per cent of the Islamic State’s suicide attacks can be attributed to foreign fighters (Neumann 2016, 104).

The flow of Muslim fighters travelling from the West to Syria happened in waves. The first wave occurred in 2012, when the civil war in Syria worsened dramatically. This was followed by a bigger wave in 2013, when it became known that the Syrian forces were being assisted by Hezbollah, the Syrian-backed Lebanese militia. Another big influx occurred in 2014, when Baghdadi proclaimed the caliphate. Nevertheless, not all Muslims from the West who went to the Islamic State wanted to become fighters—some simply wanted to emigrate (hijrah) and live in a ‘proper’ Islamic state (Koning, Moors & Navest 2016).

Although it uses foreign fighters to justify its global claims, the Islamic State’s leadership is primarily Iraqi. Al Nusra, by contrast, had a membership that is more than 70 per cent Syrian and was led by Syrians. Also, compared to the Islamic State, Al-Nusra had a more localised goal—the downfall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime (Neumann 2016, 155–56).

The Islamic State employs different models of expansion (Neumann 2016, 164–66). When it is able to, it incorporates other groups into its fold. For example, the Nigerian militant group Boko Haram eventually pledged support to the Islamic State despite being affiliated with Al Qaeda previously. Sometimes, the Islamic State benefits from splits within other jihadist groups, resulting in splinter groups switching allegiance to it, for example with the Taliban in Pakistan. It also embarks on hostile takeovers, for example against the Al Qaeda-aligned Ansar Al Sharia in Libya. In 2016, however, the Islamic State was nearly wiped out in Libya (Lacher 2017, 9). It is also experiencing territorial decline in Iraq and Syria. Yet in 2017, it made inroads into Mindanao in the southern Philippines (Allard 2017).

To make matters more complex, the Islamic State also has significant influence online—its own propaganda materials are slick and well-distributed. Yet even the strongest elements of its online presence are only partly under its control, if at all. This network has included the social media profiles of the fighters themselves (who often communicate with supporters in Europe), preachers on YouTube (who have also functioned as the Islamic State’s spiritual guides), and fans, or ‘jihobbyists’, who create the aura of ‘jihadi cool’ (Neumann 2016, 124).

It is tempting to lump all of the Islamic State’s violence together as an outcome of ‘jihadism’ or ‘Islamist radicalisation’, but this only hinders a better understanding of what is happening. It is more helpful to take into account the key factors—in addition to apocalypticism—that motivate the Islamic State. These include the fallout of the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the US-led air strikes in 2014, virulent anti-Shiism, rivalry with other jihadist groups (primarily Al Qaeda), abhorrence of ‘near enemies’, appeal to foreign fighters, and online influence.

Further Information

Academic references

Al-Rasheed, Madawi. 2007. Contesting the Saudi State: Islamic Voices from a New Generation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Beattie, Hugh. 2013. “The Mahdi and the End-Times in Islam”. In Sarah Harvey and Suzanne Newcombe (eds.), Prophecy in the New Millennium: When Prophecies Persist, Ashgate Inform Series on Minority Religions and Spiritual Movements. 89–103. Ashgate, Farnham.

Firestone, Reuven. 1999. Jihad: The Origin of Holy War in Islam. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Firestone, Reuven. 2012. “’Jihadism’ as a new religious movement”. In Olav Hammer and Mikael Rothstein (eds.), The Cambridge Companion to New Religious Movements. 263–285. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Gunther, Christoph and Kaden, Tom. 2016. “The Authority of the Islamic State.” Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology Working Papers 1–25.

Inge, Anabel. 2017. The Making of a Salafi Muslim Woman: Paths to Conversion. Oxford University Press, New York.

McCants, William. 2015. The ISIS Apocalypse. St Martin’s Press, New York.

Neumann, Peter R. 2016. Radicalized. I.B. Tauris, London.

Pall, Zoltan and Koning, Martijn de. 2017. “Being and Belonging in Transnational Salafism: Informality, Social Capital and Authority in European and Middle Eastern Salafi Networks.” Journal of Muslims in Europe 6, 76–103.

Reports by Think Tanks and Research Centres

Bunzel, Cole. 2016. The Kingdom and the Caliphate: Duel of the Islamic States. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Bunzel, Cole. 2015. From Paper State to Caliphate: The Ideology of the Islamic State (No. 19), The Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World. The Brookings Institution, Washington.

Francis, Matthew (ed.). 2017. After Islamic State, CREST Security Review. Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats.

Olidort, Jacob. 2016. Inside the Caliphate’s Classroom: Textbooks, Guidance Literature, and Indoctrination Methods of the Islamic State (No. 147), Policy Focus. The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Washington.

Popular References

Cockburn, Patrick. 2015. The Rise of Islamic State: ISIS and the New Sunni Revolution. Verso, London.

Online Documentaries

Al Jazeera English. 2015a. “Featured Documentary - Enemy of Enemies: The Rise of ISIL” (Part 1). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xsHrULpYeFk

Al Jazeera English. 2015b. “Featured Documentary - Enemy of Enemies: The Rise of ISIL” (Part 2). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4yX6pKOd19Q

Vox 2015. “The rise of ISIS, explained in 6 minutes.” Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pzmO6RWy1v8

Online News and Other Resources

Al Jazeera and news agencies. 2017. “Gunmen attack Iran’s parliament, Khomeini shrine.” Al Jazeera. 7 June. http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/06/attacks-reported-iran-parliament-mausoleum-170607063232218.html.

Allard, Tom 2017. “Ominous signs of an Asian hub for Islamic State in the Philippines.” Reuters. 31 May. Available at: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-philippines-militants-foreigners-idUSKBN18Q0OO

Allawi, Yasser and Zein al-Deen, Jalal. 2016. “One Fighter’s Recruitment – and Escape – from ISIS.” Syria Deeply. 12 May. Available at: https://www.newsdeeply.com/syria/articles/2016/05/12/one-fighters-recruitment-and-escape-from-isis.

BBC 2017. “Iraq PM Formally Declares Mosul Victory.” BBC News. 10 July. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-40558836.

Koning, Martijn de, Moors, Annelies, Navest, Aysha. 2016. “European Brides in the Islamic State.” SAPIENS. 15 Nov. Available at: http://www.sapiens.org/culture/islamic-state-brides/.

McKernan, Bethan. 2017. “93 per Cent Vote Yes in Kurdish Independence Referendum.” The Independent. 27 September. Available at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/kurdistan-referendum-results-vote-yes-iraqi-kurds-independence-iran-syria-a7970241.html.

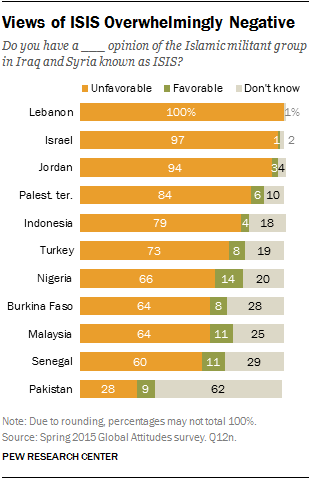

Poushter, Jacob. 2015. “In nations with significant Muslim populations, much disdain for ISIS.” Pew Research Center. 17 Nov. Available at: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/11/17/in-nations-with-significant-muslim-populations-much-disdain-for-isis/

Reuters. 2017. “US-Backed Fighters ‘Seize 80% of Raqqa from Islamic State.’” The Guardian. 20 September. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/sep/20/us-backed-fighters-seize-80-per-cent-raqqa-from-islamic-state-syria.

Tisdall, Simon. 2017. “Good News from Mosul Does Not Signal the End of Islamic State.” The Guardian. 9 July. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jul/09/good-news-from-mosul-does-not-signal-the-end-of-islamic-state.

Van Wilgenburg, Wladimir. 2017. “Who Will Rule Raqqa After the Islamic State?” Foreign Policy. 13 September. Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/09/13/who-will-rule-raqqa-after-the-islamic-state/.

Wood, Graeme. 2015. “What ISIS Really Wants.” The Atlantic. March. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/03/what-isis-really-wants/384980/.

Yates, Dean. 2007. “Senior Qaeda figure in Iraq a myth: U.S. military.” Reuters. 18 July. Available at: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-iraq-qaeda-idUSL1820065720070718

© Shanon Shah 2021

Note

This profile has been provided by Inform, an independent charity providing information on minority and alternative religious and/or spiritual movements. Inform aims to deliver accurate, balanced, and reliable data. It relies on social scientific research methods, primarily the sociology of religion. Inform welcomes feedback, comments, corrections, or further information at inform@kcl.ac.uk.